Archive for the ‘Who knows?’ Category

“Thank You for Your Service” — and Other Ways We Abdicate Our Duty

Every human being has a duty to humanity.

That’s not a slogan. It’s a fact.

We like to imagine duty belongs to the ones in uniform — soldiers, officers, firefighters — the ones who put themselves between us and danger. And we tell them, “Thank you for your service.”

But if I’m honest, I hear something else under those words:

“Thank God you did it, so I didn’t have to.”

That’s not gratitude. That’s relief wearing the mask of virtue.

Their duty does not excuse ours.

Their courage does not cancel our obligation.

Every parent, every citizen, every neighbor — every human — carries a duty that can’t be delegated:

the duty to act humanely toward other humans.

Once upon a time we knew the rule:

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Now, too often, the rule is this:

Do unto them what you imagine they’ve done unto you.

That’s not righteousness. That’s rot.

And if we keep walking that road — nursing our injuries, feeding on resentment, and calling it justice — we’ll damn ourselves.

And when we finally reach hell’s gate, even hell itself may whisper,

You’re too far gone to live here.

⸻

The Doorway in the Woods

Remembering Joe on All Saints Day, and finding again that love doesn’t end — it just changes direction.

I’ve come to think of remembrance as its own kind of liturgy — a way of practicing presence until the veil thins. This reflection began that way, on a cold November afternoon in Somerville light.

The sky was that pale, unforgiving white that settles over New England in November.

All Saints Day — a day built for remembering.

The calendar had lined itself up with Joe’s funeral again, so we went as a family — bundled against the wind — to stand a few minutes by his grave. Nothing ceremonial, just the old discipline of showing up. Letting silence say what words can’t.

Time has thinned the noise around my grief, and what’s left is simple: I miss him.

Joe wasn’t just my brother-in-law. He was a gatekeeper, a protector, and, in time, a friend forged in the odd fraternity of honor.

I can still see that first dinner — the table at Applebee’s, the air thick with steak sauce and family laughter, the eve of my marriage to his sister so near it made me clumsy. Joe watched me across the table with that steady, measuring gaze of his, as if weighing the man about to marry the woman he’d sworn to protect.

When the toasts ended, he drew me aside. His voice was low, stripped of charm.

“Listen closely,” he said. “If you ever hurt her — if you ever cause her unnecessary pain — just hear this: I know people,” his Somerville, Massachusetts accent making the words unmistakable.

It was half threat, half blessing. I understood both. Beneath the warning was love in its purest form — love that guards as fiercely as it gives. To marry her was to step inside a circle of unbreakable loyalty, and I never forgot it.

Years later, at his funeral, I met some of those people — men of quiet, intimidating bearing, the kind who keep their promises long after the one who made them is gone. By then Joe and I had settled into something easy and real. I think he knew that, too.

This year, under that washed-out sky, we stood again — his widow leaning on his son. The wind had that dry, papery sound only graveyards know. In the stillness the daughter turned to me.

“Uncle,” she said softly, “would you offer a prayer?”

I wasn’t ready. I haven’t been a public pray-er for years. The pulpit gave way long ago to the desk; spoken faith turned to written faith. My ministry now is metaphor — the quiet sermon that arrives on paper. But her eyes asked for something I couldn’t withhold.

I closed mine and waited. A recent poem of mine surfaced — about a man lost in the snowy woods of New England. He’s wandering, the trail gone, when he finds a doorway standing by itself among the pines. Out of place, yet warm light spilling from within. He doesn’t know where it leads, only that he’s drawn to it.

That doorway has become my theology: the life beyond this one as passage, not conclusion. A threshold that feels strange and familiar all at once.

So I prayed. Not a sermon, just a few honest lines. I called on the Almighty — the only name wide enough — and gave thanks for Joe: for his humor, his loyalty, his steadfast love. I invited each of us to speak to God in our own language. Gratitude more than request. Then silence again.

When I opened my eyes, the cold seemed to ease. Joe’s widow lifted her face, her hands trembling on her cane. What passed between us wasn’t thanks but recognition. For an instant she seemed to feel him near — the warmth behind that imagined doorway brushing against the November air.

I felt it too — that quiet pulse that isn’t sorrow so much as longing, the need to stay connected, to trust that love alters shape but not direction.

And under that pale sky, I understood that this, too, is prayer:

to live awake to presence,

to remember without grasping,

to keep watch for the door that opens, quietly, toward home.

—

DW, November 1 · All Saints Day

The Moral Equivalent of Starvation

By David Wilkerson

In 1978, my wife and I were an unlikely pair for poverty. I was an officer in the Navy; she was a schoolteacher in Jacksonville, Florida. For our age and time, we were well paid. We had a brand-new baby, and we left our jobs so that I could attend graduate school.

Why would anyone do that? For both of us, it was the next logical step. I believed then — and still believe now — that the Almighty, our God, had a purpose to fulfill in the world and was inviting us to take part in it. Specifically, to take on the role of a minister in the church.

We saved our money, but not enough. Not long after we arrived, I found part-time work during the day and more part-time work at night. I was in school full-time, holding down two part-time jobs. Beth, the mother of a newborn, had few alternatives. Yet the need for rent and food drove her to take a part-time job in the campus post office. So there we were — the three of us. The neighbor watched the baby when she was at work, and I was rarely home.

That still wasn’t enough. I applied for, and we received, food stamps. When I say I felt degraded and incompetent, it’s an understatement. Going to the grocery store and supplementing our payment with food stamps was excruciating and humiliating.

But without those food stamps, our meager meals would have been calorie-free.

Today, families like ours will again face that kind of hunger. Someone will say they should “get a job.” Someone will say they need to give up their avocado toast. And someone — there’s always someone — will say something unproductive and useless.

The individuals responsible for the ongoing vitality of the modern equivalent of food stamps, SNAP, have decided to use this program as a bargaining chip in their political gamesmanship.

It is self-evident that the administration and Congress are profoundly divided. But what also seems self-evident is that division has taken priority over need. Each side seeks to portray the other as the one responsible for the calamity about to descend on the most vulnerable in our society.

Let me name a few: an old man, feeble from advancing disease; a three-year-old toddler; a nursing mother; and yes, perhaps someone who took advantage of the system. But of that number, the overwhelming majority will suffer severe consequences when the program runs out of funds.

Someone will point out that there are other emergency funds available — but that misses the point.

The point is this: the only losers in this contest between Congress and the administration will be Americans. Not just those who live on the brink, but also those of us who choose to accept such behavior from our elected government.

While the most vulnerable may eat less — and eat less often — the rest of us will find our consciences further degraded. That is the moral equivalent of starvation.

I do not imagine for a moment that this little essay will have any effect on the players or the partisans. But I will not be silent.

I do not agree. I do not approve.

Shame on you.

The Uninvited Day

Some days arrive uninvited. They just happen.

Bags are packed—sometimes decades earlier—then stowed away, waiting. Waiting for the uninvited day. When it comes, the bags tumble out of their hiding places, and the contents explode into life.

Yesterday was such a day.

I had an appointment at a medical office dealing with a disease no one wishes to face. It was, in itself, rather matter-of-fact: identify the disease, consider treatment options, make decisions, do my part as a credible member of the team seeking to eradicate the problem.

But then came the baggage.

The baggage carries the awareness of mortality—not so much my own, but of those I’ve loved. Sitting in the doctor’s office, I was reminded again of how many times my late wife must have had similar conversations. Her cycle of remission and relapse always included consultations like this: the tests, the scans, the waiting for results. I was there for much of it.

Those suitcases have been familiar companions for many years.

But yesterday I unpacked another one I didn’t expect: the one I now call Morbid Math.

Morbid Math began when the doctor alluded to my advanced age, as if age alone dictates outlook. Yes, the older we get, the more we must face our finitude. But as I told him, anyone—at any age—can drop dead in a moment. Statistics may predict probability, but statistics don’t govern individuality.

This is where the science of medicine must, if practiced well, meet the art of medicine. Options may narrow with age, but every life still deserves case-by-case care.

And that’s when the arithmetic began.

In just a few years, I will have lived twice as many years as my late wife. That realization stung. I could have done without it. But the uninvited day doesn’t ask permission to unpack what it brings.

Then came another calculation. I remarried thirty-one years ago this past August. Counting the years of our courtship, Beth and I were together twenty-two years—nineteen of them married. The sheer ratio of years makes comparisons absurd. Yet I know this: Beth and I grew up together, and Lucy and I are growing down together. Each love has its own trajectory.

The problem is that growing up was interrupted. And so, I’ve spent the years since trying, in some way, to complete the work Beth and I began. I got to watch our daughters grow up. She did not.

Thank you, Morbid Math, for that reminder.

Two lifetimes, divided unevenly, yet both defining who I am. Beth didn’t just influence me—she created part of me. But she never saw the whole. In that sense, the sum is zero.

She never saw me in my entirety. I robbed her of that.

I know, unequivocally, that she would have. We were on a trajectory toward that kind of honesty. We even talked about the changes we would make to become more fully ourselves—individually and together. But the equation ended before it could balance.

So yes, yesterday was the uninvited day.

One of the worst I’ve had since the day she died.

But even this arithmetic of loss holds its strange grace: that who I have finally become—the man willing to be raw and vulnerable—is the collaborative work of two women who loved me into wholeness.

Beth began the work. Lucy has helped me finish it.

*I cannot change the sums, but I can live them. And perhaps that, in the end, is

The Little Death

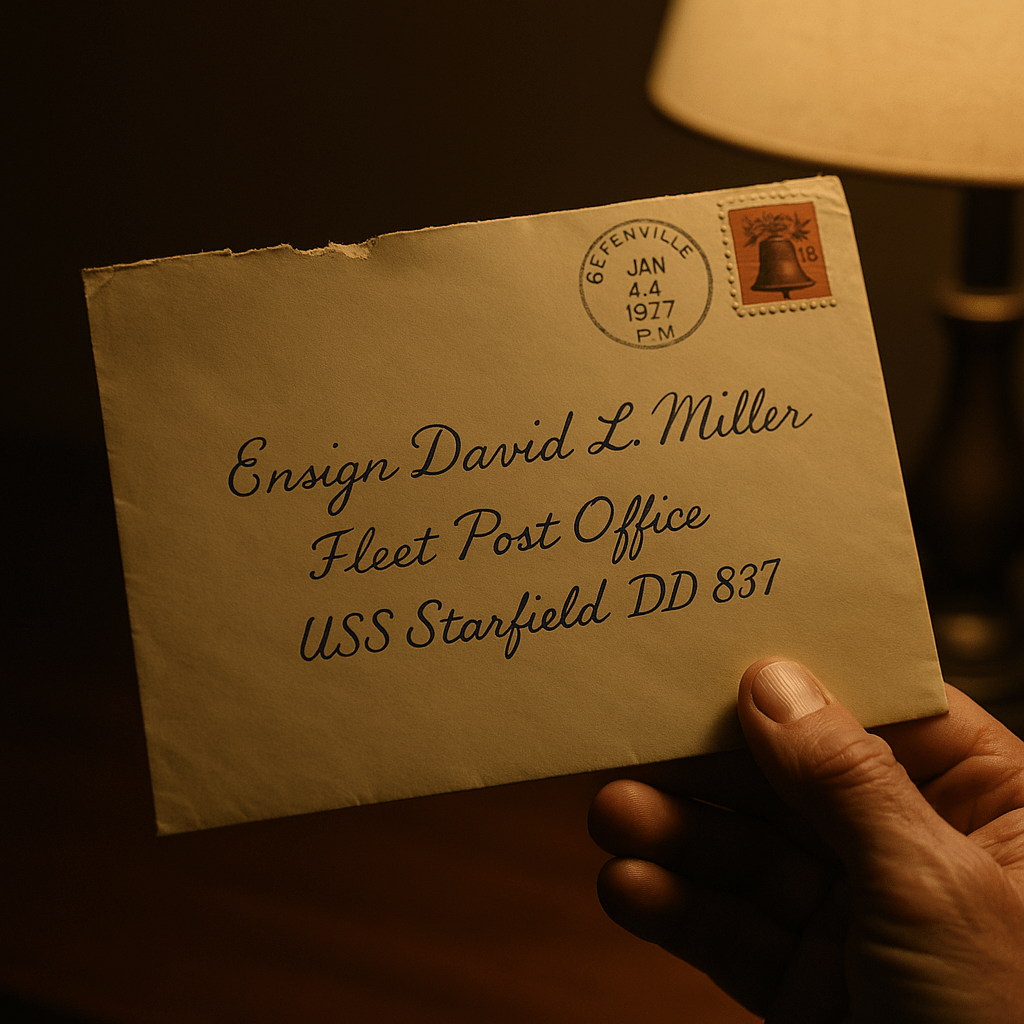

I pick up the envelope — only slightly yellowed by time. The end is torn open, as if in great haste to read what it once held. I lift it to my face, hoping for some trace of her scent, some faint whisper of the hand that sealed it.

Emotion rises; her absence floods me. My eyes follow each line of the address — her capital E in “Ensign,” the luminous D she always gave my name. Every letter is carefully inscribed: Fleet Post Office, USS Starfield DD-837.

I squint to read the postmark, my vision not what it once was. Beneath the lamplight I finally make it out: Greenville, P.M., 14 January 1977.

This was the letter she sent after her solitary journey across Europe — that audacious pursuit of adventure, and of me. I have read it countless times and never had enough. Again I’m struck by the cruel truth: there will be no more letters.

Even now — fifty years since our wedding, thirty-two since her death — the sweetness of her words undoes me. It is la petite mort in its truest sense: the tender collapse of what once was flesh and is now only memory.

I close my eyes and let it take me. The ache, the sweetness, the loss — all of it. For one breath, I hold her again. And though it breaks me, it sustains me.

— D.